For more information on fair use and the different legal systems, see Prof Brandon Butler guest blog Fair use, open norms and blurred lines between common law and civil law countries.

'open norms' on the agenda

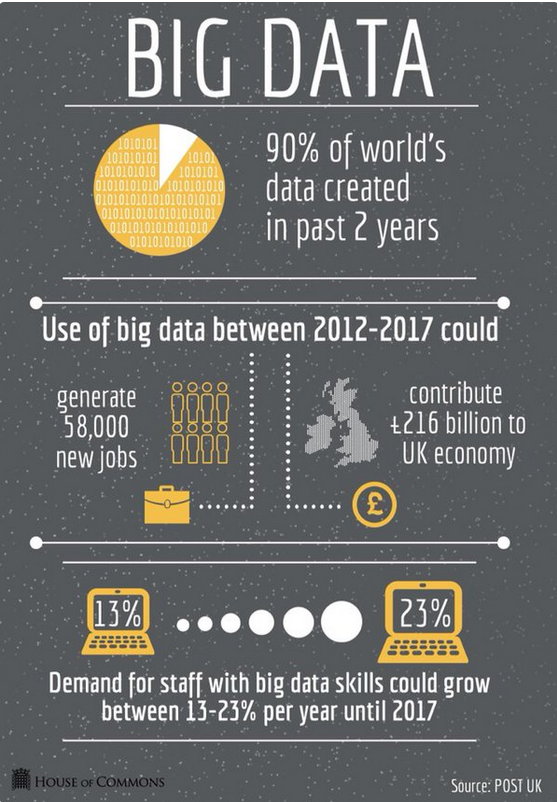

As governments seek to reform copyright law so that it is fit for the digital age, the need for a general, flexible exception (also known as an open norm) is stimulating widespread interest among academics and policy-makers.

More than 40 countries with over one-third of the world’s population already have a flexible exception (fair use or fair dealing) in their copyright law. These countries are in all regions of the world and at all levels of development.

This general exception typically exists alongside a set of specific exceptions. The virtue of a general, flexible exception is that the law can respond quickly to new uses of copyrighted works in a time of rapid technological change, including uses that were not foreseen when the law was developed, such as text and data mining.

EIFL partner countries that have fair use or fair dealing provisions in their copyright law are Kenya, Myanmar, Namibia, Nigeria, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe. (Botswana, Ghana, Lesotho and Malawi have replaced fair dealing with other exceptions).

Fair use and fair dealing in the common law tradition

The two prevailing approaches to flexible exceptions both have their roots in the common law legal tradition. The common law system, also known as ‘judge-made law’, means that decisions of the courts (collectively known as case law) have the same force of law as statutes, and act as precedent for future court decisions.

Common law originated in England and spread to British overseas territories and former colonies. Thus ‘fair dealing’ was first developed by the English courts in the eighteenth century and is now incorporated into copyright laws of many former British colonies. In UK legislation, fair dealing can be applied to works made for research and private study, criticism or review, or news reporting. Under copyright reforms enacted in 2014, fair dealing in the UK was extended to cover all types of in-copyright works (not only text based works).

The introduction of ‘fair use’ in the United States is attributed to an 1841 court decision which was based on English fair dealing case law. ‘Fair use’ was codified in the US Copyright Act of 1976. Section 107 of the Act provides that fair use for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship and research is not an infringement of copyright. Section 107 then lists four factors to be considered when determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use.

Fair use is generally considered to be more flexible and open-ended than fair dealing. A common characteristic is that the determination of whether a use is fair use or fair dealing depends on the particular circumstances of each case.

Civil law countries adopt fair use

Over the last century, fair dealing in many countries has evolved, and countries such as Taiwan and Korea with a civil (Roman) law tradition, that gives primacy to statutory law rather than to judicial decision-making, have adopted fair use.

In continental Europe, where the civil law system prevails, copyright scholars have argued that while fair use is often regarded as an oxymoron in the classic author’s rights tradition, the notion of introducing a degree of flexibility into the European copyright system is gradually taking shape.

In addition, decisions of supranational courts such as the European Court of Justice (binding on 28 EU member states) and the European Court of Human Rights (to which 47 Council of Europe member states are party) are shaping national jurisprudence, thus increasingly blurring the lines between the common law and civil law systems.

Common law v civil law systems

In practice, some countries already operate with elements of both legal systems reflecting their history and traditions, as a glance at The World Factbook uncovers:

EIFL partner countries with a civil law tradition: Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia & Herzegovina, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia, Georgia, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mali, Moldova, Mongolia, Poland, Senegal, Serbia, Slovenia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan.

EIFL partner countries with a common law tradition: Fiji, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Palestine, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

EIFL partner countries with a mixed system of civil law and common law: Botswana, Cambodia, Cameroon, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland, Thailand.

Copyright laws not keeping up with technology

We know that as libraries strive to provide effective information services to their local communities in a global information place, the laws that govern access to copyright protected content look increasingly unmanageable.

Data from the WIPO Study on Copyright Limitations and Exceptions for Libraries and Archives (2015) shows that the copyright laws in many countries are simply not keeping up with technology, with library practices or with user needs. For example, a full 40 years after the ‘Digital Revolution’ 32 countries ban the use of digital technologies by libraries, and of those that have amended their laws in the last five years, 17 countries still do not permit digital copying.

We also know from our work campaigning for national copyright law reform that anticipating each and every use of a copyrighted work requires more than a degree in crystal ball gazing, and that reforms in many cases simply mean that the law is only catching up with reality.

We also know from our work campaigning for national copyright law reform that anticipating each and every use of a copyrighted work requires more than a degree in crystal ball gazing, and that reforms in many cases simply mean that the law is only catching up with reality.

To alleviate the tension between the law and practice, to reduce the need for continuing legislative reform, and to help make the copyright system work well for everyone, it is time to seriously consider the introduction of an open norm in copyright law to benefit people everywhere.

See also ‘Fair use, open norms and blurred lines between common law and civil law countries’ by Professor Brandon Butler.

Further reading

EIFL Draft Law on Copyright p.40 Article 17C Fair dealing

The Fair Use/Fair Dealing Handbook

Fair Use in Europe: In Search of Flexibilities

Teresa Hackett is Copyright and Libraries Programme Manager for EIFL.

For more information on fair use and the different legal systems, see Prof Brandon Butler guest blog Fair use, open norms and blurred lines between common law and civil law countries.

SHARE / PRINT